Thoughts on 7 Random Movies from 2019

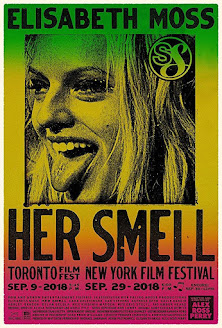

Elizabeth Moss rains fire and brimstone as the scurrilous rock goddess Becky Something, a feral, untamable beast of a character, inflicting abuse upon her band mates and inner circle. Becky’s vitriol is so intense even us, as paying audience members, can’t avoid being hit with shrapnel; she acts as if possessed by some ramped up, adrenaline-burning demon, only coming to a pause upon concussion. The role is a career-best showcase for Moss, and the film, “Her Smell”, a different stratosphere for its creator, the fecund indie workhorse Alex Ross Perry. Wide in scope, spanning a downhill slide all the way to one final stab at redemption, the film feels like a sizable leap forward from anything the filmmaker has done in the past, a bold vision seen all the way through, leaving the audience with the feeling there was no compromise, each frame as intact as first conception.

Thrashing through the first hour plus, bluntness a prerogative and erraticism a set course, the film starts with some really bad behavior, only escalating our heroine’s antics till no further escalation could be endured, by anybody on or off screen. The movie begins at a boiling point, a kettle whistling louder and louder, combustion a clear inevitability, the only available avenue. Tiresome though this strategy may feel, the payoff that follows is priceless, worth all that bad behavior we are forced to endure, watching a car wreck over, and over, and over. By the end what began as a single character narrative strikes an impression of ensemble, with equal affection felt for the minor roles as for Becky.

An amalgamation of Courtney Love and Axl Rose, Becky is the front woman for the hardcore rock trio Something She, along with Marielle Hell, played by Agyness Deyn, and Ali van der Wolff, played by Gayle Rankin. As “Her Smell” opens its curtains, the band is already on its last legs, all due to the megalomaniac behavior of its star center. The two supporting players have had enough of the shit, as the movie slowly reveals. Played out in five segments, each one broken up by old video footage of the band in their formative years, “Her Smell” takes its structural cue from 2015’s “Steve Jobs”, playing out what are essentially five long scenes, each one a luminous insight into the life of this hot mess of a self-crowned goddess. Whereas “Steve Jobs”, through its three pivotal events in the title character’s life, keeps us at an arm’s length from really getting to know the man, “Her Smell” does the opposite, investing us deep into Becky’s personal life to a point beyond sympathy, where we are wholly vested in this character’s outcome.

The long bouts of chaos in “Her Smell” reminded me of Gasper Noe’s movie from earlier this year, “Climax”, when the LSD consumed by a dance troupe takes hold and the movie turns into a one note insane asylum. In Perry’s movie, debauchery is put to functional narrative use, not simply to boast a director’s skill at shooting mass organized confusion, where many characters are playing off the domino effects of one another. Are these sequences capable of testing our patience? Somewhat, but they are always interesting, always leading to a pivotal discovery, they are means to an end, a remark I can’t ascribe to the Noe film. Tempting as it may be to pontificate how truncating each segment, even excising whole ones, would shorten the running time without loosing any effect, I believe editing a movie like this would have lessened the overall effect of its conclusion; reveling in the madness, in addition to technical impressiveness, goes a long way to prove its point. After experiencing Becky Something in all her glory early on, you’re floored when after her star power wanes she plays a piano cover of Bryan Adams’ Heaven to her daughter, or a new song penned while sober to her guitarist.

In the second segment we are introduced to another trio of female performers, all three acolytes of Something She, signed to the same label by its owner, played Eric Stoltz’s character, allowing “Her Smell” to counterbalance its abundance of negativity with some youthful optimism. Played by Cara Delevingne, Ashley Benson, Dylan Gelula, their band, the Akergirls, are a welcomed blood transfusion to the proceedings, giving Moss additional victims to feed off. Elizabeth Moss is a powerhouse here, going from unhinged to serene to walking a tightrope with the skill of an acrobat; this is easily her best role since the Mad Men.

The vibe of a director sticking to his guns reverberates in “Her Smell”. Alex Ross Perry has had an interesting voice since coming on the scene with Impolex, which I have not seen in full, continuing with “The Color Wheel”, “Listen Up Phillip”, “Queen of Earth” and “Golden Exits”, all of which I have seen. With “Her Smell”, he changes inflections fully, forming a unique dialect I had not thought possible based on those past titles. “Her Smell” feels epic and personal, a rare combination in movies these days.

Embarrassingly oblivious to the details of the Peterloo massacre, watching Mike Leigh’s new film, a retelling of the tragic event, felt intimidating, the fear of not fully comprehending the unfolding story becoming a serious factor. Luckily Leigh is skilled enough to provide apt explanations without hardcore pandering to people well versed in their British History. If all you know about Peterloo is a bunch of people gathered in a place and were killed and wounded, the movie will add ample background, placing you right in the thick of things, immersing you in rabble rousing speeches, parliamentary indignation, and the plight of those living in Northern England in the years following the Napoleonic wars.

“Peterloo” is an epic that could easily have been a streaming miniseries were it not handled by one of cinema’s enduring voices, whose consistency and singularity has not been disproven in a forty-year career. Leigh actually began his career directing projects for television before graduating to theatrical released features. Returning to a more shrunken format would not have been a first for the director, especially when dealing with historic recreations such as his latest project, a movie that justifies its 155-minute length by continually emitting steam, intensely focused on the matter at hand. Amazon forked over a significant sum for Leigh to bring this story to the big screen, the budget is well spent.

The scale of production, level of detail, voluminous cast of expert actors, all dazzling no matter how minimal their screen time, is wondrous to behold. Deftly produced recreations of monumental events are one of the best tidings movies have to offer. “Peterloo” is a mystical teleportation to the past, giving people a deep understanding of the times depicted without a hint of dullness. For most of its duration, the film does a deep dive into the bleak lives of these suffering country folk, who have to ration food if not beg for their nourishment, while landowners and those in parliament live high on the hog, paying themselves huge sums of unwarranted bonuses, not too dissimilar from the current day CEO payouts, taking in huge bonuses without increasing employee salaries. The comparison is tangible, yet Leigh never loses focus on his bleeding heart empathy for what these folk were forced to endure at the behest of a corrupt government.

Leigh makes his views easily discernable, not only in the areas paid longer focus to, the reformers taking up most screen time, but in the clearly defined good versus evil layout of greed at the expense of mass suffering. All the while, “Peterloo” feels accurate as schoolbook text.

Barring a moment or two of obvious explanations to the audience, such as when a group of newspapermen define the act of Habeas Corpus for us (which I totally knew and definitely did not need a reminder of), “Peterloo” is a glorious epic of a notch of Mr. Leigh’s film belt.

Growing up in a foreign country, moving to the US at a very young age with my parents while the remainder of my family stayed behind, I could relate to many of the emotions undergone by Billi, the main character in “The Farewell”; nostalgia for a nebulously remembered point of origin, the deep-seeded connection to a grandparent not visited in decades, acclimating to differing cultures, all this rang a bell of familiarity, one known to anyone who experienced a wide geographic shift in their formative years, yet despite the attached personal connection, much as I wanted to be on board with “The Farewell”, especially in the face of the glowing unanimous reviews its received, I couldn’t shake the feeling that this boat never leaves the dock. The hook is a good one, positing a story that promises more relational dynamics than it ultimately winds up with.

The rapper turned actor Awkwafina naturally charms as Billi, an aspiring writer from NYC who learns her grandmother in China is sick, given a grim prognosis that makes time of the essence, and books a flight to China along with her parents for one final farewell to the beloved relative. The catch is, the high-spirited grandma is oblivious of her disease, the doctor’s test results remaining hidden from her by other family members and are doctored by printing vendors to state all is benign, leaving Nai Nai (Shuzhen Zhao) with the impression of a clean bill of health. A family wedding is arranged as an excuse for a forthcoming reunion, the burden of the lie hovering over its duration.

The family’s decision to hide death’s proximity is a cultural custom, as is later revealed, one loaded with potential for explosive ramifications, yet not much of interest ever develops, the occasional plaintive sulk barely enough to rattle attention. Somber in spite of what is supposed to be a festive nuptial occasion, Billi has difficulty reconciling her family’s deception with her grandma’s mortality, her ambivalence the only interesting strand the script affords its story. Every other family member simply goes through downcast motions, nary hinting at insights of loss and grief, or offering variation of feeling regarding the ruse.

On the other hand, the cultural insights are worthy of a viewing. One of the more interesting characters is the one non-family member, Mr. Li, a living companion to Nai Nai, their arrangement less out of affection and more from a need to stave off loneliness, have another living flesh under the same roof. What “The Farewell” has going for it is Awkwafina, a personality able to carry an indie where not much happens, to the events or the characters.

A nebulous sense of danger is in effect during the beginning scenes of “Transit”, an era distorting thriller from Christian Petzold, whose last film, “Phoenix”, was one of 2015’s highest praised releases. Like his previous movie, the new one deals with identity deception in relation to a loved one, only “Transit” throws in an effective gimmick, transposing Nazi occupied France into what appears to be a more modern setting. Lazy as this may sound, as if budgetary constraints would not allow for wardrobes of the times depicted, the background trickery works wonders on the story, never interfering with our concept of what these times should look like, the appearances of automobiles and architecture of 1939 taking a backseat to the dynamic story of a young man trying to escape a country on the verge of being ethnically “cleaned”. The political specifics are intentionally murky, we don’t hear the word Nazi of Vichy uttered by anyone, for instance, yet through little tells, random housing raids and such, we are aware of timeline implication.

The melding of historical events with modernity aside, this story of prolonged fleeing from imminent catastrophe would most likely, I surmise, be sufficient on its own to equate an intriguing film, but as a combo, “Transit” reaches heights of intangible eeriness otherwise not experienced in this genre.

At the start, France is on the cusp of being sealed off; the invasion of a hostile nation intent on the clearing out of a certain people is on the horizon. Getting out of dodge is the business of the day for many, procuring visas, transit papers, and safe passage as difficult as it was for Jews in late-30’s Nazi Germany.

We follow Georg, who at first seems apathetic about the current situation, only to slowly display the cunningness of a survivalist, in his attempts to get out of the country. Given the mission of a messenger, tasked with delivering two letters to a very important writer, through happenstance, which is doled out a little too generously later on in the film, Georg winds up purporting to be the letters’ recipient, taking the dead man’s, documents, eventually even scoring a ticket out of town. The writer’s estranged wife and her lover come into play, as does the family of a deceased traveling partner Georg was paired with, both relationships making the wait until his voyage takes off fill the time wisely.

Petzold keeps the threat of thwarted plans at arm’s length, leaving us to feel the jig will be up at any moment, only to take a few unforeseen turns to confound expectations, even allowing for the audience to keep interest in the lead’s fate. There are a number of turns and twists, but none of them jarring, mostly leaving a curious complacency rather than jolted shocks. The only downside that comes to mind is an unneeded voice over, that of the bartender of a recurring location, the only eatery I think shown in the film, and it is the setting for many scenes. The voice over first appears late in the proceeding, adding no value or insight to an otherwise fascinating art house thriller.

A throwback to buddy-action movies, where the laugh are commensurate to the bullets and violence thrown around, there is not much worthy of noting in “Stuber”, a movie with the intellectual quality befitting its season of release. In other words, it gets the job done, nothing more, not that more should be expected from movies of its ilk. As long as the story moves at breakneck speed, delivering a levity borne out of the most unrealistic of situations, and the mismatched duo persist in a back and forth banter that exemplifies their differences in personality, there is not much to complain about as far as the entertainment factor is concerned. Certainly there have been plenty of poorly made movies in this genre, a dying one, as most move genres that are not franchise based are, making the success of this formulaic type action-comedy not so easy to attain. For every Rush Hour or 48 Hours there are plenty like 2005’s The Man or the Stallone starring Stop or My Mom Will Shoot.

Pairing the comedian Kumal Nanjiani with ex-WWE wrestler Dave Bautista proves a solid mismatch for this comedic equation that, for all its weightless idiocy, is more enjoyable now that these movies are made with less frequency. “Stuber” sticks to a formula that is not practiced as often on movies with theatrical distribution, one concerned only with laughs and action and entertainment, delivering the goods, as it were. Where “Stuber” loses points, as any other genre movie the sticks to proven formulas, is the quality of its gags and the lack of fluctuation in a one note premise. Not every joke has the elasticity of Stretch Armstrong, and the movie’s recursive way of playing the same premise in differing situations wears thin the more it is repeated.

Luckily, Nanjiani’s schtick hasn’t been played out, and the star of “Silicon Valley” has enough spark of freshfaced talent to sustain an interest.

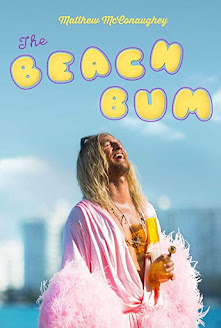

On the surface level, apparently all Matthew McConaughey seems to be doing in “The Beach Bum” is emit bursts of squealing high-pitched laughter, revealing a man heavily under the influence of multiple substances, and chain smoke joints as if the stuff were as legal as American Spirits, but unbeknownst to the naked eye, this is actually a rather immersive performance from the virtuoso actor, one of the better roles he’s undertaken in recent years. His new film pretends to a deliver an aimless plot, yet quickly stumbles upon the ridiculous stipulations that give goofball comedies like 95’s Billy Madison their charm. Just like Billy, a grown man, had to redo grades Kindergarten through senior year of high school in order to inherit his father’s company, Mr. Mac has to finish writing his magnum opus before collecting his recently deceased wife’s fortunes. McConaughey revels in playing the titular Moondog, an avowed Floridian poet who prefers the pressure free atmosphere provided by the southern most tip of the state, Key West, a place where taking it easy is the lifestyle of choice, and is apparently the only choice for Moondog. When he’s summoned by his benefactor of a wife to Miami to attend his daughter’s wedding, there is resistance to a return to the rules and regulations of modern society. And the reasons are evident, Moondog is a capricious free spirit who just as easily shoves a man off a pier as he would crack open the next Pabst Blue Ribbon. The once famous poet is a freewheeling free spirit whose sole purpose seems to be imbibing and fucking as much as possible. He’s a helluva fun screen presence whose amusing antics are a continual blast to take in, especially at the movie’s well-paced running time of 90 minutes,

It’s easy to see how “The Beach Bum” would test the patience of most critics, seeing as it is modeled on those raunchy 90’s comedies that rarely endeared themselves to the tomatometer, but for audiences that shelled out admission price to those flicks, turning them into box-office behemoths, this is a great throwback. There is plenty of gross out humor and gags to satisfy that crowd, sharks sever limbs and the odd wheelchair bound elderly get pushed carelessly onto concrete, but what really prevails is the spirit of those comedies, where rooting for the hero despite his seemingly reprehensible nature is a common thread. Logic, sensibility, they fall to the wayside in favor of mean spirited silliness.

Coming from Harmony Korine, a staple of indie lore, this may seem like an odd choice. There are zero remnants from his early movies like Gummo and the Julien Donkey Boy present here. If anything The Beach Bum is closer stylistically to Spring Breakers, his one breakout hit. The two are visual companions, each offering a diverse mood, attuned to a Floridian sensibility.

Pulling on a perennial joint while reciting inane poems from his former glory days, it’s hard to believe Moondog was once considered to be brilliant, a stoner version of Bukowski. It’s a concession that that should be willingly made.

When watching a remake, upgrade, reimagining, or whatever polished version of older source material, the difficulty is to not experience the movie simply as perfunctory elements delivered with gloss. Although a new sheen is applied, we as an audience know what to expect, which can be problematic in rousing our interest. You expect an adaptation of familiar material to hit certain markers. At times a filmmaker will adapt a well-known novel, transposing vital plot points to suit their own interpretation, making the source simply a jumping point for their own vision to be taken wherever they see fit. So what makes the difference between a really good remake like 2017’s IT and the new Pet Sematary? Both have been updated to meet the fast paced standards of today’s audience, yet the latter is abominable dreck, while IT is one of the best horror films to be unleashed upon the mainstream in some time.

The horror elements fail to congeal into anything resembling fright here until the final 10 minutes, at which point containing your laughter at the absurdity of the filmmaker’s failure to believably convey what is one of the more interesting horror concepts is a difficulty of its own. Laughter is the farthest reaction wanted from directors Kevin Kolsch and Dennis Widmeyer, who set up a greyly grim landscape to coincide with the elemental death motif.

This new Pet Sematary is a bland, lifeless, truncated rush job of King’s excellent paperback. Although the previous big screen adaptation did not have set the bar high, now we have to limbo. Setting up the premise believably is the crux of all the film’s issues. When the kindly old neighbor to our family’s main character discovers the young daughter’s cat mangled by the side of the road, the assistance he offers the father of “taking care of it” is mechanical beyond robotics. John Lithgow, an underused actor of diverse skills, plays the neighbor, and its one the most glaring throwaway performances of his career. “Ellie loved that cat, right?” he asks the father right before they bury the rotting feline in dirt damned by evil. “Yes”, the father responds. “And you love Ellie?” is the follow-up question, one that easily could have been excised from the novel’s cinematic translation.

Such laughably implausible dialogue is only the beginning, soon we’re inundated with visions of a recently deceased victim of a hit and run the father tried saving who fruitlessly acts as his spiritual admonisher, advising him to leave his new digs at once.

There’s nary a saving grace in this new remake, full of cheap scares that couldn’t budge the least seasoned of scary movie buffs. The 100-minute running time barely permits the story to explore the fascinating concept of reviving the dead, particular a lost loved one, and the ramification of all that that entails.

Comments

Post a Comment